Preface

Microplastics is a very challenging topic. The research I did for this piece scared me in a way that I have not been scared by research before. I came to fully understand how immersed we are in microplastics on a daily basis, but how little we know about their effects, and how little we can ever know about how much and what kinds of plastics and, importantly, plastic additives, we are exposed to. Like all of us, I want some control of what goes in me and my family. The impulse I’m feeling at the moment is to avoid all plastics, but one look around me, and I know that is quite impossible.

Optimistically, when I put the issue in context, my sense is that microplastics is a long game problem, and the game has just started. There are more urgent and important food and health concerns in the near term, but we can’t ignore what is happening with plastic. The more quickly we react to the new microplastic environment we live in, the sooner we will understand the priorities for action, for us as individuals and for our society.

At the end of this piece I would be quite interested in your reactions to all of this in the comments section.

The story

In 1951 an efficient way to make polypropylene and high-density polyethylene plastic was discovered by Philips Petroleum chemists searching for a way to turn Philips’ huge holdings in natural gas into a profitable product. Polypropylene and high-density polyethylene are the numbers 5 and 2 in the recycling triangles on the bottom of many containers in your kitchen. Recycling number 1 is PET and is found on the bottom of soda bottles and prepared food containers. PET is a polyester, like the fiber in clothes and rugs. Together those three plastics are the most common of the six main types.

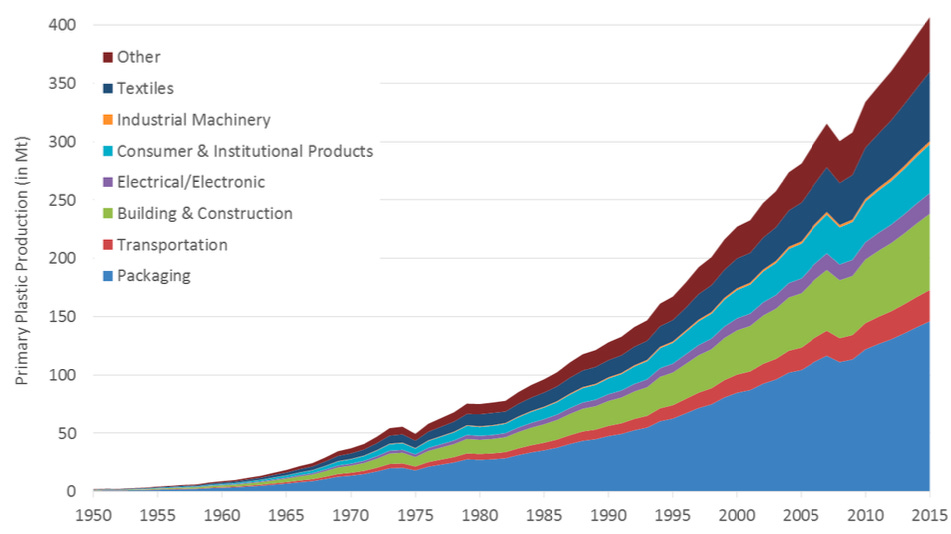

The manufacturing of plastics has been exploding since 1951, when 2 million metric tons of plastics were made, globally. In 2015, ten years ago, that annual figure was near 400 million metric tons. In 2017, half of all plastics ever made were produced in just the prior 13 years, between 2004 and 2017. And the trend keeps zooming upward.

Packaging for consumer products and food is the biggest user of plastic, 40% or 50% by some estimates. Other major sectors are building and construction and textiles.

Plastics production grew so quickly from the 1950s that by 2004, marine biologist Richard Thompson reported on the vast quantity of plastic waste in the ocean and the presence of something he termed “microplastics.” In the space of 50 years the developed world had created a global plastics crisis.

What exactly are microplastics, and how about nanoplastics?

Microplastics are primarily shed from larger pieces of plastic, although some are manufactured at a micro or nano level, such as microbeads used in personal care and cosmetic products. Microplastics are defined as ranging from 5 millimeters (a little less than ¼ inch) to 1 micron (or one-millionth of a meter) in length. Nanoplastics are all the smaller particles down to the limits of detection technology, below 100 nanometers. Nanoplastics can easily pass through the lungs and intestinal lining to enter the bloodstream, where they can travel to and enter our organs, but microplastics are found in our organs as well. Secretary of Health RFK, Jr. has correctly identified that these micro- and nanoplastics can be “…found in samples of human tissue: in the brain, the liver, the kidneys, the colon, the placenta, and testicles.” Nanoplastics are small enough to enter into individual cells.

Where do microplastics come from?

Breakdown of waste plastic creates 22% of microplastics in the oceans. Worldwide, in research where a brand on plastic waste could be identified, of the top 10 sources of plastic pollution in 2023, six were ultraprocessed food companies: Coca-Cola (perennially the top source of plastic pollution), Nestlé, PepsiCo, Mondelēz, Mars, and Danone. Two other top sources, Unilever and Procter & Gamble, specialize in body care and other products. The last two sources in the top ten were tobacco companies: Altria Group and British American Tobacco. The cigarette culprits are the filters in the butts thrown on the ground.

There are three main paths into our bodies from packaging plastics like soda bottles and baby food containers. First, particles are released into the environment and then we eat or drink them in our food and water. Second, we inhale them. Third, our food and water packaging releases microplastic directly into the food and water we are preparing to eat and drink. Additionally, nanoplastics from personal care and cosmetic products can enter through pores and abrasions in the skin and have been shown to cause skin cell damage, but skin contact is a minor entry point compared to the mouth and nose. Fortunately, one source of micro-and nanoplastics intended for skin contact, microbeads, were banned from certain personal care products like toothpaste and facial scrubs, first in 29 state laws and then in federal law in 2015.

Other major sources of microplastics in the environment include vehicle tire wear particles, which are bearers of toxins from the tires, and microfibers from laundry water after the washing of synthetic fiber clothes. City dust, a mix of plastic particles, is another leading source.

A team of scientists in China wrote somewhat poetically about the sources of microplastics:

“The presence of microplastics can be detected from the Tibetan Plateau to the Marianas Trench and from the houses we live in every day to the untouched skies over the Pacific Ocean.”

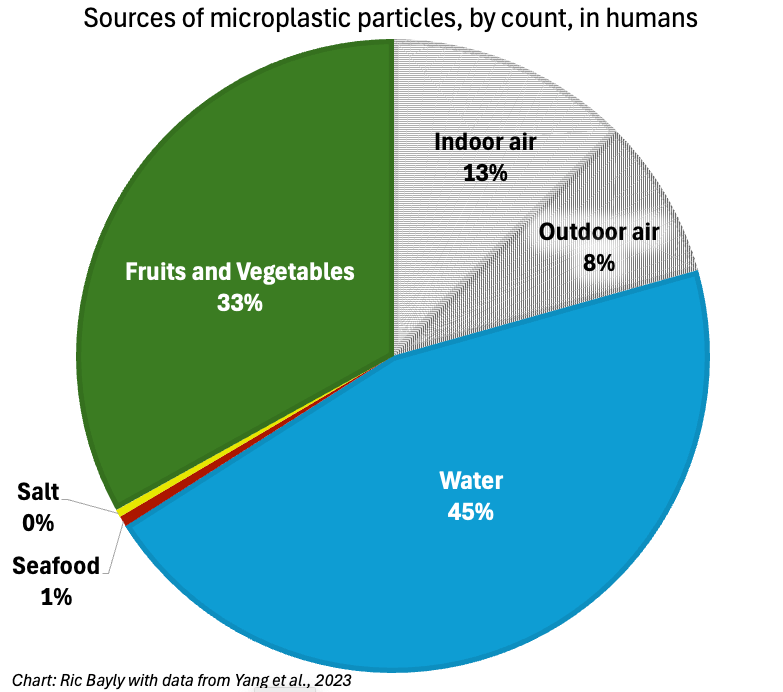

Their analysis, along with analyses by others, found drinking water, food, and inhaled air were the major sources of microplastics in humans.

Research published by the National Academy of Sciences estimated that a one-liter bottle of water contained over 100,000 plastic particles, 90% of them nanoplastics.

Our poetic Chinese scientist friends estimated that of the microplastics counted in the body, 45% came from water, 33% from fruits and vegetables, and 21% from indoor and outdoor air, but more from indoor.

The quantities estimated to come into the body on average from food, water, and air might vary greatly depending on the methods of different researchers, and they will vary for each individual according to their environment. The consistent finding is that micro- and nanoplastics are everywhere, and we eat, drink, and breathe them.

Why are micro- and nanoplastics harmful?

Microplastic particles are rough and irregular in shape and porous. They gather pollutants like bacteria, viruses, heavy metals, PCBs, pesticides, and carcinogenic polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, which are the products of the incomplete combustion of coal, oil, gas, wood, and tobacco. Once in your body these free riders can be released.

The rough particles can act like splinters and damage tissue.

And then there are the additives. The global plastic additives market approached $50 billion in 2020.

The most worrisome effects of microplastics in the body are from the release of the chemicals added to them when they are made. Of 13,000 additives to plastic, over 3,000 are concerning because they are persistent, accumulate in tissue, or are known or potential toxins. Many more of the chemicals might be toxic, but they haven’t been studied.

Some of the worst chemical additives that we know about include:

Bisphenol A, or BPA, which is used in metal cans, plastic food containers, reusable water bottles, and water pipes. BPA can be regarded as a potential human carcinogen. It’s an endocrine disrupter, a reproductive toxin, can pass through the blood-brain barrier, and is linked to nervous system disorders and degeneration. BPA has toxic genetic and epigenetic effects. It’s not good for your DNA.

Phthalates are used to make plastic flexible. Phthalates are linked to endocrine, reproductive, respiratory, and nervous system problems.

Styrene, a building block of plastics, is a known carcinogen in California and a reproductive toxin.

Brominated flame retardants, including PBDEs, are used in recycled plastics for household goods and toys and are a concern for nervous and reproductive systems.

Other known toxic chemicals released by microplastics include PFAS, PFOS, and triclosan, a germicide used in toys and kitchen utensils, and in toothpaste in the U.S. until about six years ago. Triclosan is a reproductive toxin and endocrine disrupter.

What does RFK, Jr. say?

In September 2023 presidential candidate Robert Kennedy had a list of ten almost idealistic promises to reduce plastics in our lives. These promises embraced and then went far beyond the Democratic supported Break Free from Plastic Pollution Act of 2023, which failed to pass in either chamber of Congress.

Kennedy promised to:

Support an international plastics treaty

Restrict toxic plastics and chemicals

Prfomote a national bottle bill

Require producers to take responsibility for their pollution

Upgrade recycling facilities and systems

Limit new plastic production facilities

End subsidies for plastics producers

Order a major national study to evaluate all sources of plastic waste

And, most radically, to ban fracking, which provides most of the natural gas America produces, and thus the raw material for the plastics produced here

Were the promises ever to be enacted a huge reduction in plastic production and use would follow, along with reduced release of microplastics and reduced plastic contaminants and pollution. Of course, the fossil-fuel friendly Trump is never going to ban fracking, nor would most of the other proposals seem likely to be approved by the business-friendly Trump.

In fact, Kennedy’s ambitions about plastics have been greatly scaled back. At a meeting in April with representatives of packaging manufacturers, Secretary Kennedy simply asked industry to voluntarily reduce plastic use.

While Secretary Kennedy has otherwise been somewhat silent on microplastics, at the same meeting he said, quite accurately: “We don’t know the effects of microplastics in the human body, but we have disturbing studies that link microplastics to cancer, dementia, and reproductive problems.”

Kennedy’s Make American Health Again Strategy Report, released in September, made one mention of microplastics, but only in a long list of other health risks to be researched prior to action:

“[Health and Human Services], in collaboration with NIH and EPA, will complete an evaluation of the risks and exposures of microplastics and synthetics, including in common products such as textiles.”

What to do about it on a personal level?

We are exposed to plastic, microplastics, and nanoplastics from all directions every day, and no individual can know how best to reduce their plastic-related health risks or even what those risks are, if any.

At one end of the long list of possible action items is going to Europe for a $10,000 microplastic blood filtering treatment – yes, that’s a thing! But I prefer to start by throwing out my plastic spatulas.

There’s actually some consensus on a best first step, which you likely already know: avoid heated plastic, especially when it contains food. As of 2024, U.S. manufacturers have phased out their use of PFAS to grease-proof paper and paperboard containers used to contain food, so take-out containers are less concerning now than they were. However, I’m still trying to figure out what to do about hot take-out food, since even paperboard containers are still usually lined with plastic or wax. There is no really good answer beyond giving up take-out, but that is not going to happen soon in my house.

Here are some other solid, low- or no-cost, steps, though.

Check your tea bags. Some well-known brands still use plastic bags, which can release 11 billion microplastics and 4 billion nanoplastics into one cup of hot tea. Maybe hold the sugar after that! Brands that don’t use plastic bags include Republic of Tea, Numi, Yogi, Pukka, Bigelow, Stash, Traditional Medicinals, and more lately, Lipton, and Twinings.

No plastic should go in the microwave. Cover foods in glass bowls with a plate or use a silicone vented-cover during microwaving. Just know, silicone is a polymer, as are plastics, and, like plastic polymers, has additives that can migrate out. Most of what migrates out of silicone are siloxanes, the building blocks of silicone. Several siloxanes are listed by the European Union as “substances of very high concern,” due to potential carcinogenic or mutagenic risks. Nonetheless, silicone compared to plastic is more stable and heat resistant and considered safer, especially compared to plastic when heated.

Wash and dry synthetic fabrics (polyester, nylon, acrylic, and spandex) on the cool cycle and maybe lean toward natural fibers in new clothes. Microplastic fibers can come loose in the laundry and may stay on your clothes and be available for you to inhale. But most of them will end up in the ocean.

Stainless steel or protected glass water and hot beverage containers are recommended over BPA-free plastic.

Wood cutting boards are preferred over plastic, especially because of the knife action on the surface.

Epilogue

In recent decades, our civilization has invented a very large number of new substances and, using these substances, new products, many with a wealth of undeniable benefits. Much of our amazing, life-saving medical technology depends on plastic, for example. But downstream from all of this invention, we often learn of associated health risks, which unfold over time.

As these worrisome risks become revealed, some people tend to shy away from the related substances and products. Take Teflon for example.

My office is my front porch, where I take breaks from Eating in America to check out the birds visiting the birdbath and to say hello to the neighbors.

It was 38 degrees Fahrenheit this morning, and I was sitting here in my three jackets and warm blanket writing this article, the fresh air helping the coffee to wake me up and keep me going. I turned on my new radiant heat lamp to “high” to keep my fingers warm enough to type.

At the suggestion of a reader, I was checking the status of Teflon (or PTFE, the chemical abbreviation for Teflon), still for sale 11 years after the toxic chemical PFOA was removed from Teflon in new frying pans and other products in the U.S. My heater began to give off a noxious smell – just as I found in my research that radiant heat lamp bulbs in heaters such as mine are often coated in Teflon to make them more shatter-resistant. The off-gassing of PTFE from such bulbs kills poultry when used to warm the birds…So now my hands are cold as I wait to hear back from the heater company about whether their bulbs are coated in Teflon.

Ironic! I was researching a toxicity in the kitchen that we might want to avoid while I was possibly inhaling the same toxicity from a completely unexpected source. Not just ironic but a case in point for the state of our personal environments. We are surrounded, and if we turn from one chemical or substance, we will encounter another to reckon with.

By the way, there is evidence that DuPont’s replacement of the toxin PFOA in Teflon with another PFAS they called GenX, may be worse. GenX causes cancer in lab animals. Our non-stick pans are going in the trash.

In fact, 3M, DuPont, and other PFAS manufacturers knew in the 1940s, soon after Teflon began to be used in products, that PFAS chemicals were linked to health risks. They hid their knowledge from the public until a lawsuit forced their disclosure.

This may feel gloomy, and I’m sorry. Maybe I should start a microplastics-worry support group.

Figuring out how much exposure we have to micro- and nanoplastics is a massive scientific challenge, and knowing any associated risks approaches impossible at this point. Microplastics are tiny and tasteless so, perhaps for now, make yourself a nice cup of tea or pour yourself a Chardonnay to go with your Thanksgiving leftovers, and damn the microplastics. I hope you had a great holiday. At our house we gave thanks for true science, public health professionals, and healthy food!

And I give thanks to Jennifer Rappaport, a reader and experienced health writer, for advice about Teflon.

And thank you for listening. Please subscribe if you haven’t and share this and other Eating in America posts. If you care to start a microplastics support group in the comments, or just offer your thoughts about microplastics, please do.