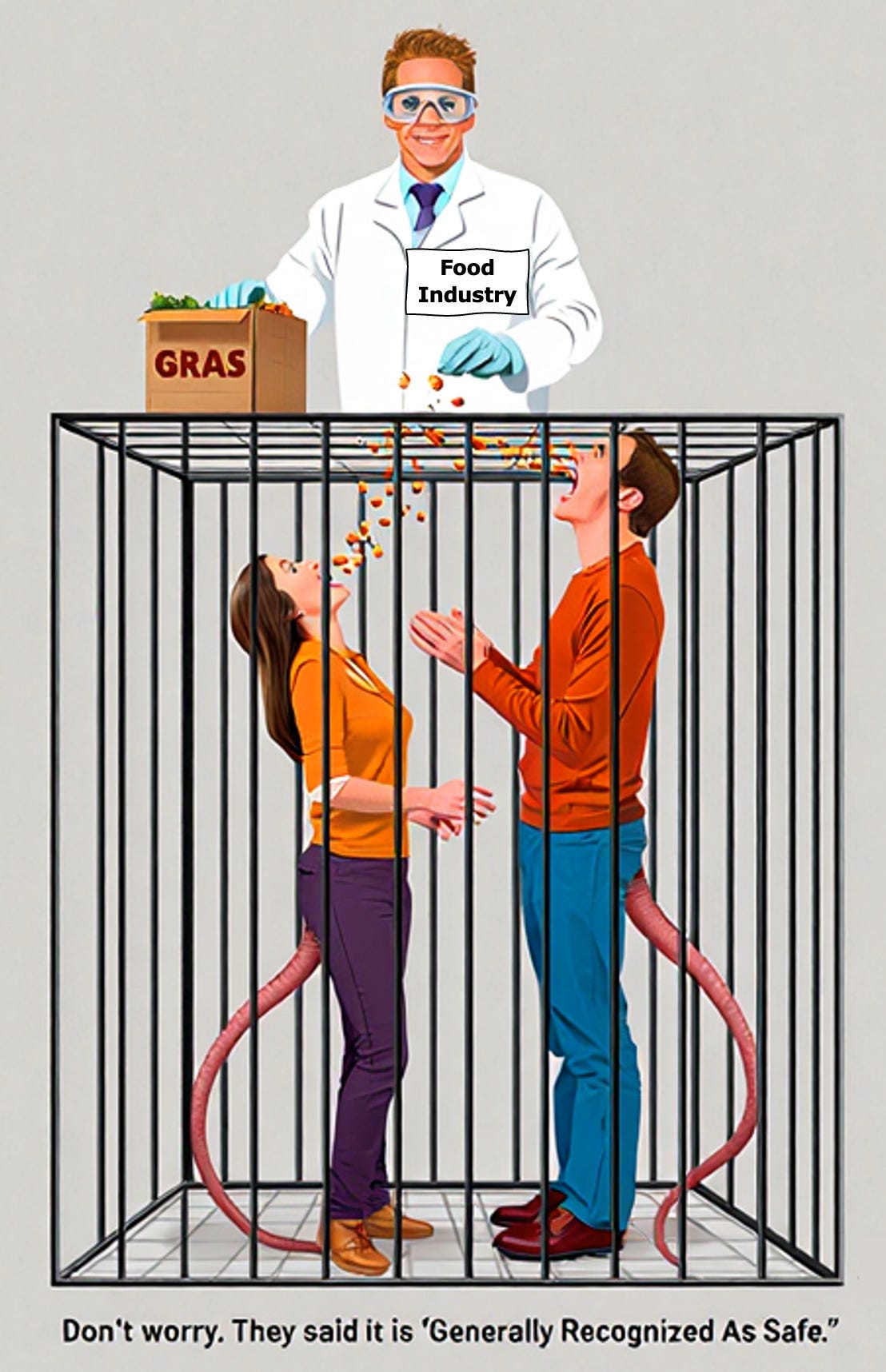

The Food and Drug Administration’s oversight of food safety has a giant loophole, really a series of giant loopholes, allowing cancer- and chronic-disease causing food ingredients to reach American plates every day. Secretary of Health and Human Services Robert F. Kennedy, Jr., who has oversight of the FDA, made clear his dismay about this back in March:

“For far too long, ingredient manufacturers and sponsors have exploited a loophole that has allowed new ingredients and chemicals, often with unknown safety data, to be introduced into the U.S. food supply without notification to the FDA or the public.”

RFK, Jr. is right. He is talking about the “Generally Recognized As Safe”, or “GRAS”, status: the heart of a broken food additive oversight system. In 1958 Congress passed a law meant to streamline approval of common ingredients that were already in use, in order to focus on new ingredients. The 800 or so ingredients on the initial GRAS list included household substances like salt and sugar, along with lab-produced chemicals like the artificial sweetener cyclamate.

FDA’s oversight during this period, worked, sort of. In 1970 the FDA banned cyclamate on the basis of contested evidence that it might cause cancer in humans. On the other hand, strong evidence has accumulated about the health harms of too much salt or sugar, but the FDA so far refuses to take up the question of revoking the GRAS status of these substances when consumed in levels beyond those recommended by the science.

What has appalled RFK, Jr. and nutrition scientists and policy makers alike is the direction that food additive oversight took at the FDA in 1997. That is the year in which the FDA turned over the responsibility for assessing the safety of new food ingredients to the food manufacturers themselves, without them being required to turn over any safety data to the FDA. Consequently, for the last 27 years, food ingredient creators could make their own, private determination of GRAS, using any method they chose, without letting anyone know they were adding a new ingredient to the food supply.

Since 1997 about 1,300 notices of new GRAS ingredients have been provided voluntarily to the FDA but without any safety evidence. Incredibly, if the FDA flagged any concerns with such a notice, the manufacturer was free to withdraw the notice and introduce the ingredient into the food supply anyway! And it is likely that hundreds or thousands of products have been declared GRAS by manufacturers and introduced into the food system without any notice at all to the FDA or public. Since there is no public notice of these new ingredients, there is no way of knowing how many there are or what they are.

This is the mess Kennedy would like to clean up, and so on March 10th he instructed the FDA to explore how to eliminate the GRAS pathway to introducing a new substance into the food supply.

But is GRAS really all that bad? Let’s look at some examples.

The FDA maintains a database of the 1,300 or so ingredients that food additive manufacturers have notified the FDA that they, the manufacturers, have self-affirmed as GRAS. Most of the ingredients, especially those added more recently, have chemical and scientific biological names consumers won’t recognize. A recent example is “Algal oil (≥40% docosahexaenoic acid) from Aurantiochytrium limacinum H Sc-01”. The notice for this oil, submitted by a Chinese intermediary company, is for a mix of triglycerides containing 40% or more of a beneficial omega-3 fatty acid, DHA. Theoretically good for you.

This oil is manufactured from micro-algae – the green stuff on ocean rocks and in waters and wet surfaces everywhere – and is intended as an additive for baby formula. The FDA responded to this notice in June, saying it was not judging safety, which was the responsibility of the manufacturer to determine, but that the FDA had no questions, case closed. I’m not in a position to judge whether there is anything scary about this particular manufacturer’s notice of a food additive they are making from algae to be sold for baby consumption. However, it is certainly scary that this notice and hundreds more like it have been filed with no offering by the manufacturers of any evidence of safety and no safety review by the agency in charge of food safety, the FDA.

Mycoprotein is made from mold, a fungis, and is on supermarket shelves as Quorn, a meat substitute. The creator of Quorn, Marlow Foods, asked the FDA to approve it as a food additive, but when the FDA did not make a decision, Marlow withdrew the petition, declared they had determined Quorn was GRAS, and started to sell it. Since 2002 over 2,900 reports of allergic and gastrointestinal reactions to Quorn have been recorded by the Center for Science in the Public Interest. Among these reports was that of an 11-year old boy with a known mold allergy and asthma who died after eating Quorn. When he stopped breathing, he could not be revived by an EpiPen and had no pulse. Paramedics arrived and brought back his heart beat, but the boy died in the hospital the next morning. After eating Quorn, a 16-year old Swedish girl with asthma died following two days of effort to revive her in the hospital. Many other hospitalizations were reported as well.

As with cyclamate, some GRAS determinations have been revoked, but not before plenty of harm was done. Partially-hydrogenated oils, or trans-fats, were very popular and used widely at home and in restaurants. However, scientists calculated that trans-fats had been causing 50,000 heart attack deaths each year. In 2013, the FDA finally revoked the GRAS status and in 2015 banned trans-fats.

Of the GRAS products we know about – and, remember, all of the undeclared GRAS substances are an unknown unknown – there are many for which scientists have found evidence they are, or may be, unsafe. Consumer Reports’ top candidates for GRAS revocation include, and sorry for all the chemical names, I’ll hurry through them:

brominated vegetable oil, used in sports drinks and sodas, is linked to nervous system, thyroid, heart, liver, developmental, and reproductive problems

potassium bromate, a flour improver, is linked to cancer

propylparaben, a preservative, is linked to reproductive issues

titanium dioxide, a food coloring, is the mineral that makes paint white and that is used in sun block for our skin; titanium dioxide is linked to DNA and cell damage and cancer; a recent study found titanium dioxide nanoparticles omnipresent in human, animal, and infant formula milk.

What are the prospects for elimination of the GRAS system, for needed FDA funding for oversight in the face of massive job cuts this year, and for the removal of politics and commercial influence in what should be scientific and health protection decisions?

RFK, Jr. has taken a baby step towards eliminating the GRAS system, but its replacement is in question. Congress and Trump are unlikely to restore FDA funding Trump removed, let alone increase it to appropriate levels. FDA Commissioner Marty Makary lied, or failed to examine the cuts he made in his department, when he said no scientists were fired in the 2,000 jobs abruptly axed in April. And political and commercial control over science has become overt in the Trump administration and Kennedy’s Health and Human Services department so little hope of improvement there.

However, there are a couple of sparks of hope. In August, Former FDA Commissioner David Kessler filed a 60-page petition full of scientific evidence that the sugars, flours, starches, and additives used in ultraprocessed food are unhealthy in ultraprocessed food and therefore cannot be GRAS. This is a petition that should be making RFK, Jr. happy. If the FDA follows it own rules, the ultraprocessed food industry would suffer a great blow. However, the ultraprocessed food industry spent $1.15 billion on lobbying, 1998 to 2020, the most of any group in America, so, in my mind, the odds are good the FDA will never respond to the GRAS questions involved.

The more promising spark of hope are the moves by California, New York, and Illinois to ban specific food additives like propylparaben, or even, in New York’s case, to require evidence supporting GRAS status before a new ingredient could be sold in the state. In 2023, California banned Red Dye No. 3, along with three other food additives. Perhaps spurred by the California ban, in January the FDA banned the use of Red Dye No. 3 in food and drugs.

A functional, funded food safety system could make a significant difference in our nation’s health, because so much of our chronic disease is associated with what we are sold on eating. If only the FDA picks the big targets: salt, sugar, and refined flour and starch, in combination with the additives to ultraprocessed food.