Editor’s note: Eating in America officially launches today, so we’re celebrating something most of us love – coffee! Or tea, of course, if you prefer. The voices of 11 Eating in America readers are heard in the audio/podcast version of today’s Eating in America, making it a very good day to try the audio version, if that is not your usual choice. Thank you for being a part of Eating in America as we officially launch!

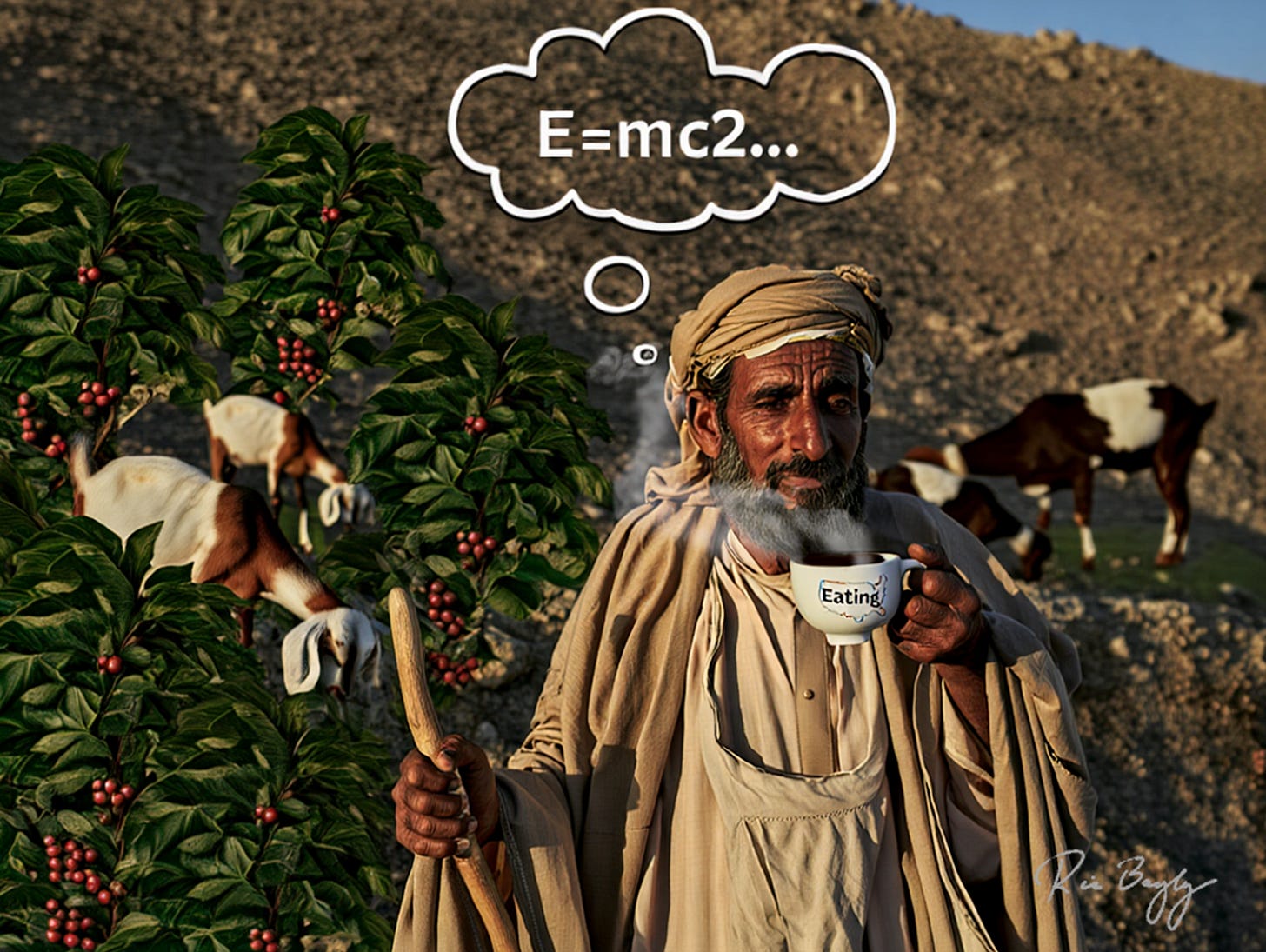

I propose that the Nobel Prize for Science should be given posthumously to the goatherd Kaldi, who, 1,300 years ago in Ethiopia, observed his goats were getting very happy after eating the berries off what turned out to be a coffee bush. Kaldi’s discovery of coffee was a great leap for humankind and probably directly responsible for much of the scientific discovery to follow. To paraphrase the G.O.A.T. (that is, Greatest Of All Time) physicist Albert Einstein and the mathematician Alfréd Rényi, who was the first to say it, people are just machines to turn coffee into intelligible thought.

In even the briefest history of coffee, it is important to identify the heinous role of enslavement. It is horrible that, as with two other addictive substances, sugar and tobacco, the explosion of coffee consumption in the Western world was enabled by the kidnapping and enslavement of people from Africa. Outright slavery was used in large producing countries like Haiti and Brazil, and the coercive semi-enslavement of indigenous people made Central American coffee planters rich.

On the positive side, according to many studies, brightening our minds and our days with coffee or caffeinated tea does not seem to bring a health penalty, on balance, for most moderate users. Some studies show coffee linked to a possible reduced risk of some cancers, although one study shows an association with an increased risk of lung cancer. A study reported this past summer but not yet peer reviewed and published found a modest association between coffee drinking and healthy aging, although the study only involved women who were white. A good review of caffeinated beverage consumption published this summer covers not only biological effects but the societal framework of caffeine beverages, globally. That study examined the potential negative effects of caffeine consumption but still concluded the physical and cognitive performance benefits, as well as modest associations with the reduction of chronic disease risk, favored caffeine consumption for many people.

That all said, what we really need to know about coffee and tea is within the stories we keep in our memories and tell our friends. I received 19 coffee and tea stories to share from 12 people, all of whom are represented here. Together they reaffirm who we are and help reveal what we make of coffee and what coffee makes of us. And these stories open windows so we can see what we share with others. Here are the stories told to Eating in America.

If you’re a coffee drinker, the first two stories will likely strike a note of familiarity.

Joan Higbee in Maryland wrote:

“We went to visit my husband’s family who were all big drinkers. I didn’t drink much that evening and went to bed early. The next morning, I developed a huge headache like a hangover, and I couldn’t figure out why – I barely drank. The next morning the same thing. It was only after breakfast I found out that my sister-in-law had been serving us decaf coffee. I was mad. The rest of them deserved hangovers. I didn’t.”

Mary Waters was in California in grad school, working long hours, trying to produce a book. Having developed a terrible headache and worried she might have a brain tumor, she was referred to a specialist.

[Mary’s voice]

“So I got to go to the neurologist, and he did this whole workup on me. At one point he asked me, after he had done a lot of tests, do you drink coffee? And I was like, yes. Like how many cups? I said, well, I don’t know how many cups, but I make three pots. And he’s like, and when do the headaches start? And I was like, you know, after I drink three pots of coffee.”

Needless to say, the doctor told Mary she didn’t have a brain tumor but she really had to cut down on the coffee.

Chris Williams grew up mostly in Oklahoma and Columbia, South America, the daughter of an Air Force pilot, and reports her story from Texas. Chris found out, as she went off to sophisticated San Francisco to study to be a sociologist – someone whose job it is to understand cultural differences, that the coffee you drink, and how you drink it, can be a signal of differences between people:

[Chris’s voice]

“My coffee stories are both about culture. My first coffee story is about when I started graduate school, and I was very poor. But I also was very unsophisticated in my taste. So I got a job working at the Berkeley Journal of Sociology, and I brought my little hot pot and my Nescafé with me. My little jar of Nescafé, and I just thought that was normal. All of my fellow graduate students just thought I was the most exotic human being ever. Very unsophisticated. Like I just rolled in off the turnip truck or something like that. Meanwhile, they are all drinking these giant cups of Peet’s coffee that seemed to be half, half and half.”

“And you know, I did the calculation, and I figured that was a dollar a day. And that was huge. But you know, the culture, the cultural message was that I was doing something very taboo. So I quickly learned to invest the dollar on the giant cups of Peet’s coffee. And indeed it was more delicious.”

Chris’s San Francisco had the heritage of being the western U.S. coffee center from the start of the mid-1800s coffee boom, with Folgers Coffee there making leaps in the quality of beans bought from Central and South America. Folgers also led the way in the packaging of pre-roasted coffee, coffee previously having been roasted in the consumer’s kitchen just prior to brewing. Founder James Folger basically invented the consistently good cup of coffee. Ironically, the attitude about Nescafé that Chris found in San Francisco, the epicenter of the coffee explosion in America, was the opposite of what she had encountered growing up in Columbia, the source of fine quality coffee beans:

[Chris’s voice]

“Well, I lived in Columbia when I was a high school student and a lot of people there drank Nescafé, which was kind of surprising. So there I think the class meaning of Nescafé was different than it was in the States, more like a class marker that you were kind of at a higher level.”

Chris’s time in Columbia was in the mid-1970s when Nestlé’s, the manufacturer of Nescafé, was using grossly unethical and deceptive marketing practices to convince women in low- and middle-income countries, including Columbia, to feed their babies powdered Nestlé’s formula mixed with water instead of breast milk. By 1981, in places around the world where the drinking water was unclean, over 200,000 more babies died per year than in places with clean water. Nestlé’s, with full knowledge of the danger, was selling formula in places where few homes had a washing facility to clean a bottle and no clean water source. I’ve been to some of these places, and seen many of these homes, and it is still an issue. But a mother spending money on formula was seen as a sign she was doing the best for her baby, despite the cost.

It is no surprise that, with the giant marketing effort Nestlé’s was making in places like Chris’s Columbia, drinking Nescafé, instead of delicious Columbian coffee, was also seen as a marker of prosperity.

A 2023 series of papers on breastfeeding in the respected medical journal, The Lancet, reports that sales of formula to low- and middle-income nations continues, at a pace of $55 billion, annually. Today, less than half of infants and children around the world are breastfed as recommended by the World Health Organization.

Nestlé’s flipped the script in Columbia, turning Nescafé, a product made in a factory from cheap beans, into a food favored by Columbians over their beautiful native coffee beans. Moreover, Nestlé’s manipulated millions of mothers into feeding their babies formula, when scientists and international health organizations have been loud and clear mothers should breastfeed, as is possible for the vast majority of mothers. These two examples shine a bright light on what has happened here in America, where Nestlé’s and the rest of Big Food have convinced us to eat highly processed food which isn’t healthy for us.

I think of Starbucks as a place to grab a good-tasting black coffee at the airport. As I sip, I feel close to the mountains of Columbia. In reality, Starbucks is more of an ultraprocessed food giant akin to Nestlé’s than our friendly partner with a mission to wake us up, gently and deliciously. The revenue drivers for Starbucks are its blended beverages with long lists of ingredients with chemical names. Nestlé’s, by the way, is the worldwide distributor of Starbucks products outside of Starbucks cafes.

Sandy Waxman from Illinois reached a point when what coffee she drank became a badge for who she was…and Sandy is with me now in grabbing a coffee before getting on the plane at the airport:

[Sandy’s voice]

“When I turned 40, I thought I’m 40, I’m at a really big turning point in my life, I am going to stop doing things that I just don’t love, and that always make me feel bad. One was wearing shorts, and the other is drinking airline coffee. And I stopped, and it was really liberating, and I loved that.”

Wayne Quillan grew up in Upstate New York and related his coming of coffee age story:

[Wayne’s voice]

“When I was probably 10 or 11 years old, was the first time that I tasted coffee. There was some kind of event at the school auditorium. They had opened the cafeteria, so coffee was being served. And a friend of mine, Robbie, who was already a very excitable character, got himself a cup of coffee at the ripe old age of 10 or 11 and insisted that I try it. And I tried it, and I remember spitting it out thinking it was the most vile thing I had ever tasted, even though he had added copious amounts of sugar to it. And of course the next day, Robbie missed school. So I felt somewhat vindicated that I had had the good sense to not consume this awful stuff.”

Wayne went on to relate that he got all the way through late nights studying at college drinking only water, still repulsed by the idea of drinking vile coffee, even when he spent his Junior year in France living with a family who served café au lait every morning, which he didn’t touch. Only his first job after college, spending all day looking for errors in computer program printouts, drove Wayne to coffee.

[Wayne’s voice]

“It enabled me to get through the day without falling asleep, so that is where I became addicted to coffee and have been ever since.”

Coffee can be at the center of the culture of a whole community. Rocio Calvo, who grew up in Spain, where she developed her love of her “morning fix”, began to understand this while living in a small community in the mountains of Guatemala:

[Rocio’s voice]

“The time I spent in Guatemala, in a community that grew the coffee, collected it, to see the whole process … not only of the coffee [production] itself, but how the life of the community revolved around coffee. I learned how to appreciate the drink and the coffee besides my morning fix.”

Melissa Hernandez-Jasso from Mexico City was just a girl when her eyes were opened to what coffee could mean to some other girls:

[Melissa’s voice]

“My favorite coffee story is when I was a kid, I was in my grandparent’s village in Mexico along the southern border with Guatemala. It’s a small town called Guatimoc. You can Google that. I was once looking at children coming back from the mountains, they were collecting coffee. And they were carrying these big bags of coffee that weighed, I don’t know, how many pounds. And I was just so surprised to see people my age carrying that and working that way when, yeah, I just had a very different life in Mexico City with my parents.

And my grandfather told me you should try to carry that. And so I did. I tried. I couldn’t even lift any single, like, centimeter. And I was just so surprised. And I guess that always stuck with me of how effort and work there is involved in coffee. And it also instilled a high sense of class consciousness in me.”

Like Melissa’s story, the most poignant stories involved childhood memories and parents or grandparents and put coffee and tea in the center of family traditions and culture. Paul Blackborow recalled:

[Paul’s voice]

“I grew up in England, so primarily a nation of tea drinkers when I grew up there. But my mother was ornery about such matters, and she only drank coffee. But back in the 60s when I first became aware of this, there was really no ground coffee that anybody drank, certainly not in our social stratum. And so she drank instant coffee. Nescafé Gold Blend if we could afford it. Otherwise, it was the supermarket brand, Sainsbury’s, I think. Us kids would make her coffee when we made a cup of tea. And that involves spooning a spoon of Nescafé into a cup, boiling the water in the kettle and on the stove, of course, because electric kettles hadn’t been invented. And then she drank the coffee, gratefully.”

Steve Bussolari, who grew up in Connecticut, remembers a piece of advice from his father:

[Steve’s voice]

“When I was in my early teens, starting to drink coffee, my father counseled me to only drink it black, to learn how to drink it black because, the way he put it, you’re going to be at meetings. People are going to be searching for cream and sugar, not going to find it. They’re going to be all upset. But you’re going to be happy. You’re just going to go up to the coffee urn, get a nice cup of black joe, and be happy. To this day, I tell him that was the only piece of advice that I found actually useful.”

Martin Button remembered his family’s ritual of sharing tea when he was growing up in New Zealand:

[Martin’s voice]

“Tea is not really tea unless it’s brewed in a pot. This idea of tea bags, where I think everybody drinks tea out of tea bags these days, that doesn’t really count as tea. There’s a ritual about making tea that involves a good teapot, perhaps a very pretty tea cozy to keep the teapot warm while the tea is steeping, putting boiling water into the teapot before the tea goes in so that the teapot is hot and not cold when the tea goes in. Of course, leaf tea out of a container with a teaspoon in it to measure one teaspoon per person, one for the pot. And then the water is boiled and added to the pot. The lid goes on, the cozy goes on, the appointed amount of time elapses, and three minutes later, the tea is poured out, cups lined up.”

“That’s the way to make perfect tea. Growing up, when we would visit grandparents or aunts and uncles, that’s just how tea was made.

I didn’t really know about tea bags until I came to this country.”

Jessica Daniels shared a coming of coffee age story from growing up in New York with her grandparents from Poland nearby:

[Jessica’s voice]

“When I was young, my grandmother used to give me little sips of coffee, but on the other hand, my grandparents also told me that drinking coffee would stunt my growth, and I’ve never been taller than five-four. So, there you go.”

Bahaa Fam’s grandmother was Egyptian. Bahaa’s memory of her roasting coffee, says it all:

[Bahaa’s voice]

“My best memory of coffee is that when I was about three years old, my grandmother lived with us. She was a very lovely woman, very smart and very small in stature. And every morning she would get up, and she would fry coffee beans on the stove. It would fill the apartment with this incredibly wonderful smell, which I remember to this day.

And when I got married, I told my wife about this experience. And we went out, and we bought a coffee roasting machine. We run it every other day and roast coffee. And when I smell that smell, I think of the warmth I felt with my grandmother in the house with us and the delicious odor of roasting coffee in our little apartment.”

There is so much that could be said about coffee and tea. We heard from our guests about the way they used and enjoyed, or maybe at first didn’t enjoy, coffee and how coffee and tea helped bind them into their families and the communities they were a part of.

To wrap up by returning to the goat theme, the G.O.A.T., again Greatest Of All Time, baroque musician Johann Sebastian Bach, said,

“Without my morning coffee, I am just like a dried-up piece of goat.”

Thank you for listening. Please add your coffee, tea, or any caffeinated beverage story in our comments below! Links to facts used in this podcast are in the text version.

Remember, you can’t buy happiness, but you can buy coffee and tea, and those are pretty close!